Will Senator Murkowski Block EPA Action on Climate?

An amendment Senator Murkowski (R-AK) is likely to introduce is getting some attention in climate policy circles. The measure—expected to be added to important legislation needed to raise the debt ceiling, due to be considered by the Senate this month—would strip the Environmental Protection Agency of much of its authority to regulate greenhouse gases (GHGs) during 2010. Despite the attention, I don’t think the amendment is at all likely to become law. Even if it did, it probably wouldn’t have much effect on what the EPA will do over the short term. I’m not even sure that the impetus behind it is a desire by Sen. Murkowski to block EPA regulation.

An amendment Senator Murkowski (R-AK) is likely to introduce is getting some attention in climate policy circles. The measure—expected to be added to important legislation needed to raise the debt ceiling, due to be considered by the Senate this month—would strip the Environmental Protection Agency of much of its authority to regulate greenhouse gases (GHGs) during 2010. Despite the attention, I don’t think the amendment is at all likely to become law. Even if it did, it probably wouldn’t have much effect on what the EPA will do over the short term. I’m not even sure that the impetus behind it is a desire by Sen. Murkowski to block EPA regulation.

Before explaining why I think those things are true, let’s take a quick look at what the amendment would actually do. Sen. Murkowski hasn’t introduced it yet, but she introduced a similar measure to an environmental bill last fall. It was defeated. The new amendment will probably be very similar or identical. It will likely be very short, and do only one thing: remove the EPA’s authority to regulate GHGs from stationary sources under the Clean Air Act (CAA). It will only block this authority for one year, and it will not touch authority to regulate mobile sources.* Read More

Post-Holiday Post-Mortem: Surveying the Wreckage of COP-15

If I may, I’d like to start with a holiday-appropriate metaphor. Let’s pretend that you are convinced you’re getting a pony for Christmas. You’re absolutely sure of it; the momentum built up from the Christmas presents of years past is too strong for this year’s gift to be anything but a pony. As the year creeps closer to Christmas morning, you see warning signs that suggest you might not get your pony this year. Mom and Dad are struggling to make ends meet, the pony market is down overall, and you live in a high-rise apartment. Regardless, you keep thinking that pony is coming because it has to. This is the year of the pony.

When Christmas comes, you rush downstairs to find … no pony. All you got was a pair of socks. They’re nice socks. Thick and warm, they’re made of SmartWool, so they’ll keep your feet dry. They will be great socks to wear the day when you eventually get a pony. Your friend, who wasn’t expecting to get anything for Christmas got the same socks and is actually pretty stoked, considering he didn’t expect to get anything. It doesn’t matter to you, though, because you had your heart set on a pony and all you got was a stupid pair of socks. Worst December ever. Read More

Looking to 2010

With 2009 waning and 2010 revving up, it’s an opportune time to reflect on the stories, issues and ideas that shaped the climate debate in 2009 and look forward to its evolution in 2010.

Put a cap on it. Capitalizing on a democratic majority and working with interests across the ideological and economic spectrum, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi—with undeniable assistance from Rep. Henry Waxman—managed to pass historic climate and energy legislation in the House in June, 2009.

But since its passage, the bill has struggled to move forward in the Senate, taking a back seat to financial and health care reforms. And despite a tri-partisan effort and momentum from Copenhagen, late last week, Sen. Mary Landrieu, D-La.—speaking on behalf of some half-dozen moderate Democrats—said she can’t stomach a fight over cap-and-trade legislation.

Meanwhile, compelled by a 2007 Supreme Court ruling and recent endangerment finding, the EPA is moving concurrently to mitigate emissions of some six dangerous greenhouse gasses. Many, including business leaders and even EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson, say this regulation is less than ideal. But in the absence of congressional action, the agency will proceed with its policy development. Still, plenty expect the outcome to be different than expected.

Why Copenhagen Avoided a Legally Binding Treaty

Before we all explode in wrath and despair over the Copenhagen conference’s failure to pursue a legally binding climate agreement, let’s pause to remember that a legally binding agreement never was possible. There are two reasons—the United States Senate and China.

Before we all explode in wrath and despair over the Copenhagen conference’s failure to pursue a legally binding climate agreement, let’s pause to remember that a legally binding agreement never was possible. There are two reasons—the United States Senate and China.

The 1997 Kyoto Protocol was a legally binding treaty to limit the emissions of greenhouse gases, but the United States never ratified it and China, as a developing country, was not subject to its limits. The Obama administration cannot get a Kyoto-style treaty though the Senate. As for China, it has repeatedly made clear that it will not accept any limit on its emissions that might crimp the rapid growth of its economy.

Kyoto was essentially a European idea, and it is in Europe that the support for a successor treaty has been strongest. Kyoto and the American reaction to it illustrate different concepts of law, The Europeans, after more than a half a century of highly successful experience with the European Union and its predecessors, are well accustomed to the idea of aspirational law that sets a goal or standard with the understanding that member states may take some years to climb into compliance. American law has a harder edge, carrying an assumption that it is enforceable immediately on enactment, with consequences for violators. One objection to Kyoto among Americans, and not only in the Bush administration, was that it depended upon little more than moral suasion for enforcement. To Europeans, drawn by the enormous incentives to belong to the European Union, moral suasion suffices. But for an agreement that would affect most of their country’s manufacturing industry and much else, American politicians do not find moral suasion nearly good enough.

I Spent $100 Billion and All I Got Was This Lousy National Communication

For most climate policy scholars, analysts, advocates, and makers, the last gasp before a much-needed two-week break will be trying to make sense of what happened in Copenhagen, and what it means for the short-and long-term global response to climate change. It would be easy to get bogged down in analyzing the chaotic process that produced the Copenhagen Accord, but I will focus on what the outcome means for the United States cap-and-trade debate over the next several months.

For most climate policy scholars, analysts, advocates, and makers, the last gasp before a much-needed two-week break will be trying to make sense of what happened in Copenhagen, and what it means for the short-and long-term global response to climate change. It would be easy to get bogged down in analyzing the chaotic process that produced the Copenhagen Accord, but I will focus on what the outcome means for the United States cap-and-trade debate over the next several months.

New Research Tackles Climate Change Governance Impasse

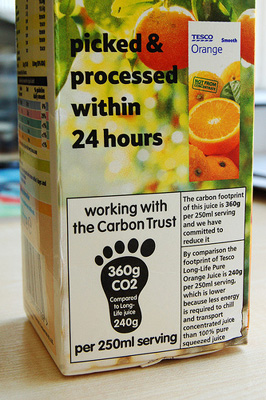

This week’s U.N. climate talks highlight the gulf between developed and developing nations. Responsibility for emissions reductions, monitoring, and enforcement are the tragedy of the climate change commons. Despite commitments set, or delayed, in Copenhagen, new research from RFF Vice President and Senior Fellow Mark Cohen and Vanderbilt University Law Professor Michael Vandenbergh suggests that corporate reporting of carbon emissions and carbon product labeling could be crucial tools to help solve the governance dilemma.

This week’s U.N. climate talks highlight the gulf between developed and developing nations. Responsibility for emissions reductions, monitoring, and enforcement are the tragedy of the climate change commons. Despite commitments set, or delayed, in Copenhagen, new research from RFF Vice President and Senior Fellow Mark Cohen and Vanderbilt University Law Professor Michael Vandenbergh suggests that corporate reporting of carbon emissions and carbon product labeling could be crucial tools to help solve the governance dilemma.

Major developing countries such as China and India are projected to account for 80 percent of global emissions growth in the next several decades. Meanwhile, carbon-intensive production continues to shift to labor abundant developing nations, creating what economists call leakage. In a forthcoming article published by New York University’s Environmental Law Journal, Climate Change Governance: Boundaries and Leakage, Cohen and Vandenbergh propose corporate carbon footprint disclosure and carbon product labeling as a means to incentivize emissions reductions among suppliers even in the absence of government regulations.

Hopenhagen?

![]()

In this post, University of Gothenburg economics professor Thomas Sterner chronicles his journey to and through Copenhagen. From troubling policy framework to Hopenhagen, Sterner says as long as the world is talking about the troubles of climate change, there’s still reason to hope.

COPENHANGEN — I took the three-hour train trip from Gothenburg to Copenhagen without major illusions. Although I prefer to be an optimist it is clear that a good, viable, treaty is not within easy reach during this meeting. Positions on basic issues such as finance are too simply far apart. The most basic issue is, of course, the allocation of emission allowances or abatement burdens.

The news media constantly offering up information on different country commitments to emissions reductions—Japan 25 percent, EU 20 percent, maybe 30 percent, USA 14 percent to 17 percent. Then they start asking, “What will India do?”

Cross-Nation Consensus on Covering Costs of Changing Climate

As negotiations in Copenhagen seem to take two steps back for every two steps forward, it’s easy for observers to despair about there being a policy solution to the world’s problems with climate change.

One issue continually in the news is that large fractions of people in the U.S. do not believe in climate change and, by implication, would not be willing to pay to reduce the emissions that cause it; another is the perceived fairness of how the economic burden of reducing greenhouse gases should be divided among countries.

Yet, despite these national-level opinion polls, little is directly known about the willingness to pay to avoid the consequences of climate change in the U.S. and whether it differs among countries. This willingness can be taken as a barometer of the strength of political support for costly mitigation actions.

Can the CDM Make You Happier? Just Ask Bhutan

![]()

COPENHAGEN — The concept of Gross National Happiness is one that, while having been coined in the early seventies, is still in a somewhat crude stage (at least to the quantitative at heart). When I heard that the Clean Development Mechanism was being touted as a way to help maximize GNH, I naturally had to check it out.

The term Gross National Happiness (GNH) is attributed to former King Jigme Singye Wangchuck of Bhutan. Having initially made its appearance in the early 1970s, one would think the idea has been translated into a quantitative form and used to assess just how well of Bhutan actually is, not so. While the idea does have several main components that comprise it, there is not, as of yet, an objective measurement that can be used in the decision making process of governments. Regardless of these facts, the idea is alive and well in Bhutan.

A recent side-event here in Copenhagen was devoted to the various projects that are being considered by the government of Bhutan in order to maximize their Gross National Happiness, with project financing made available through the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM). The emissions reductions that the government seeks to obtain result from substituting fuel consumption of rural households with that of carbon-free electricity use. In Bhutan then, the CDM is looked at not simply as a way to make money, but also as a way to increase the overall happiness of the country itself.

The Environmental Gender Gap

Copenhagen negotiators aiming to reduce the world’s carbon emissions will need to bridge the gap between developing and developed nations. Closing the gender gap may be one of the key ways to achieve those reductions.

Copenhagen negotiators aiming to reduce the world’s carbon emissions will need to bridge the gap between developing and developed nations. Closing the gender gap may be one of the key ways to achieve those reductions.

Women worldwide are more likely to support environmental policies and are often the ones making eco-conscious decisions for their families. Last year, the OECD concluded in a report that women were more likely than men to support government policies to reduce emissions, such as carbon taxes. They are also more likely to buy sustainable products with a Fair Trade seal.

Advocates for sustainable development, which encompasses economic, environmental, and social factors, want to ensure that this eco-friendly sentiment is rewarded with equal opportunity for employment. According to a recent draft report by the International Labour Foundation for Sustainable Development (Sustainlabour) and UN Environment Programme, at least 80 percent of new global green jobs are expected in the construction (retrofitting building, transport infrastructure), manufacturing (fuel-efficient vehicles, pollution control equipment), and in energy production sectors. Women hold less than 25 percent of the world’s manufacturing jobs, including non-labor intensive computer and machine operation.

Subscribe; to our RSS Feed

Subscribe; to our RSS Feed Tweets by @RFF_org

Tweets by @RFF_org

Recent Comments